[Epistemic status: work in progress, at least insofar as I haven’t really nailed down the type-signature of “factors” in the general case. Nevertheless, I do this or something like this pretty frequently and it works for me. There are probably a bunch of prerequisites, only some of which I’m tracking, though.]

This posts describes a framework I sometimes use when navigating (attempting to get to the truth of and resolve) a disagreement with someone. It is clearly related to the Double Crux framework, but is distinct enough, that I think of it as an alternative to Double Crux. (Though in my personal practice, of course, I sometimes move flexibly between frameworks).

I claim no originality. Just like everything in the space of rationality, many people already do this, or something like this.

Articulating the taste that inclines me to use one method in one conversational circumstance and a different method in a different circumstance is tricky. But a main trigger for using this one is when I am in a conversation with someone, and it seems like they keep “jumping all over the place” or switching between different arguments and considerations. Whenever I try to check if a consideration is a crux (or share an alternative model of that consideration), they bring up a different consideration. The conversation jumps around, and we don’t dig into any one thing for very long. Everything feels kind of slippery somehow.

(I want to emphasize that this pattern does not mean the other person is acting in bad faith. Their belief is probably a compressed gestalt of a bunch of different factors, which are probably not well organized by default. So when you make a counter argument to one point, they refer to their implicit model, and the counterpoint you made seems irrelevant or absurd, and they try to express what that counterpoint is missing.)

When something like that is happening, it’s a trigger to get paper (this process absolutely requires externalized, shared, working memory), and start doing consideration factoring.

Step 1: Factor the Considerations

1a: List factors

The first step is basically to (more-or-less) goal factor. You want to elicit from your partner, all of the considerations that motivate their position, and write those down on a piece of paper.

For me, so far, usually this involves formulating the disagreement as an action or a world state, and then asking what are the important consequences of that action or world-state. If your partner thinks that that it is a good idea to invest 100,000 EA dollars in project X, and you disagree, you might factor all of the good consequences that your partner expects from project X.

However, the type signature of your factors is not always “goods.” I don’t yet have a clean formalism that describes what the correct type signature is, in full generality. But it is something like “reasons why Z is important”, or “ways that Z is important”, where the two of you disagree about the importance of Z.

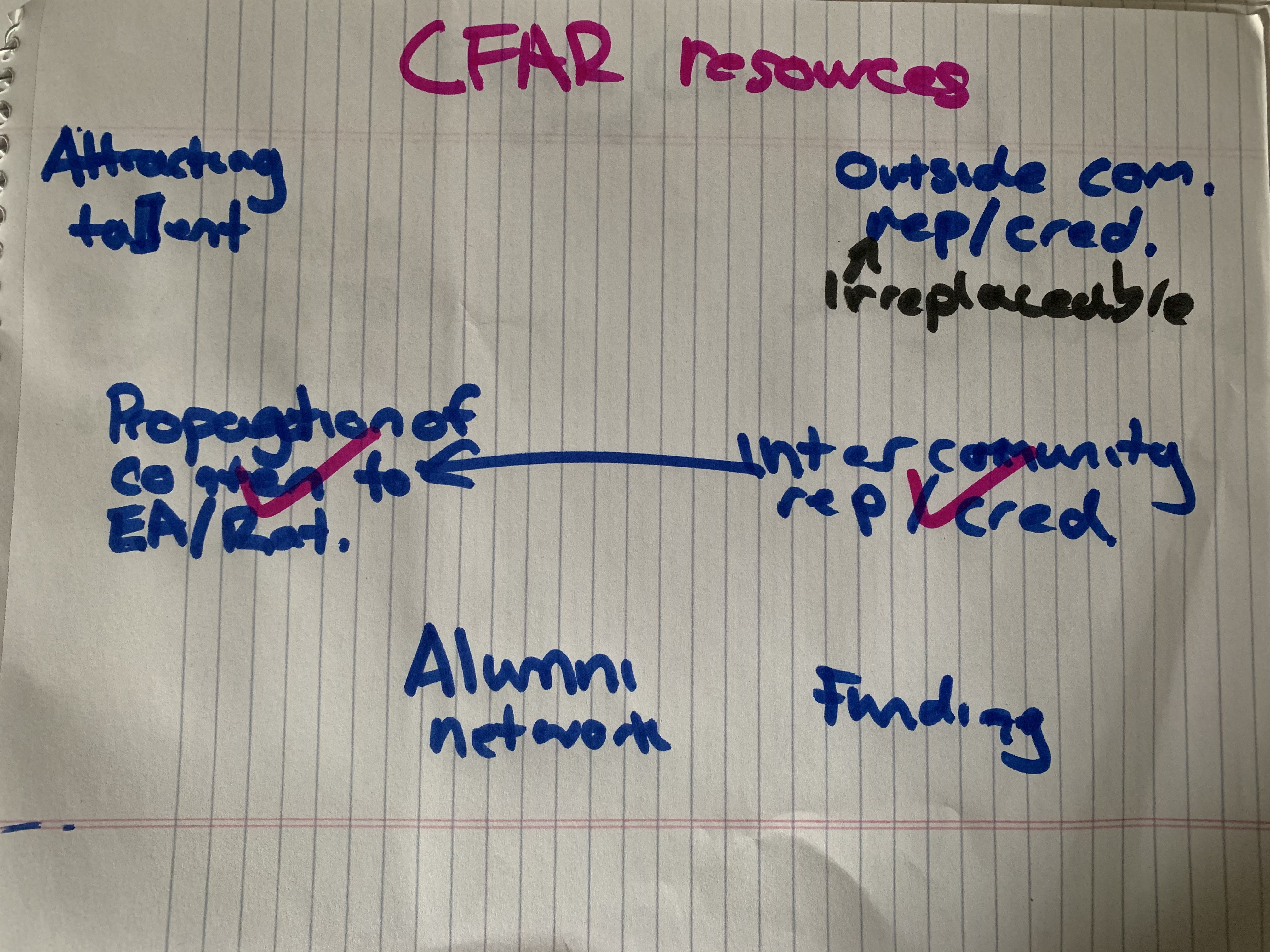

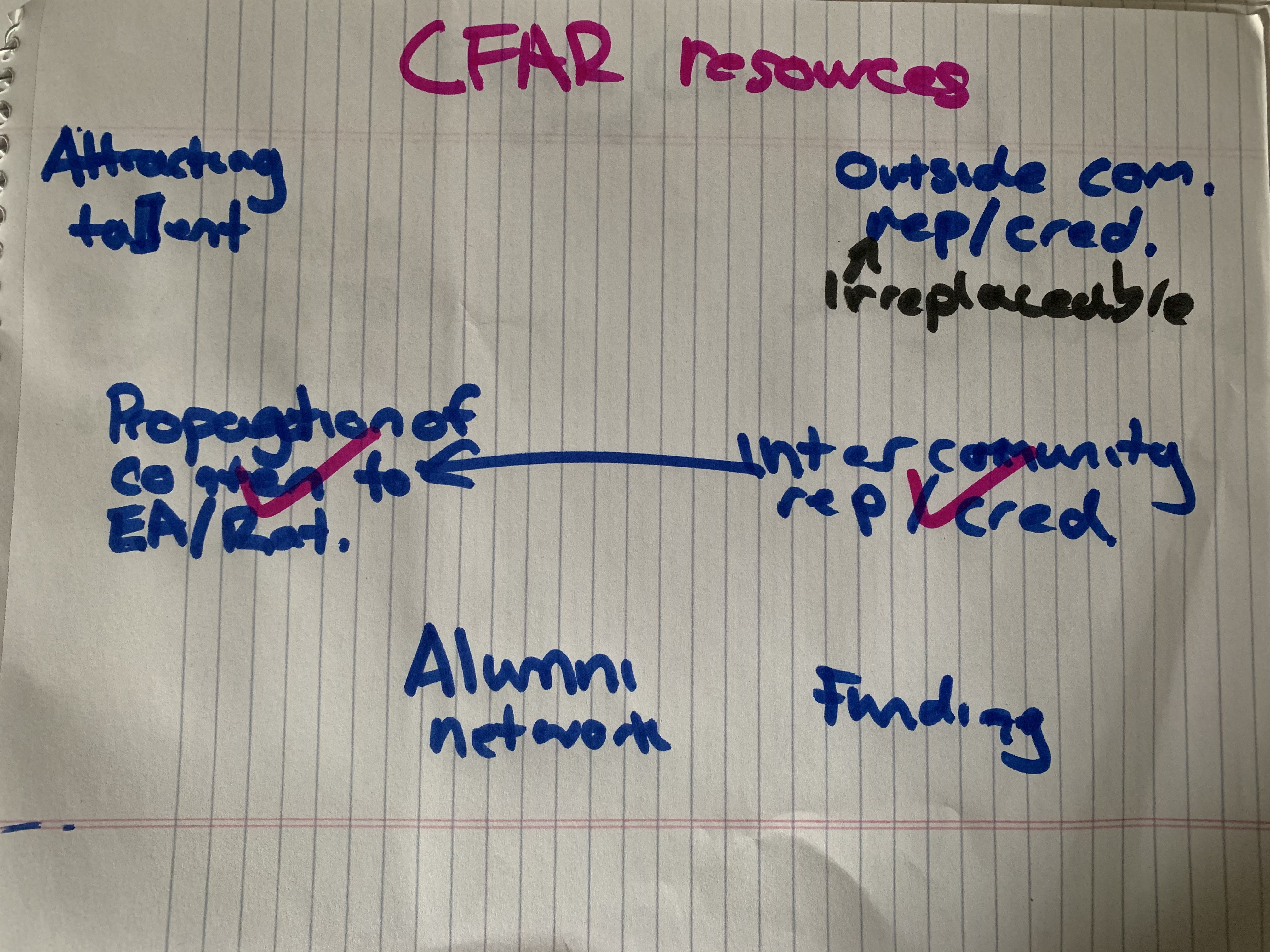

For instance, I had a disagreement with someone about how important / valuable it is that rationality development happen within CFAR, as opposed to some other context: He thought it was all but crucial, or at least throwing away huge swaths of value, while I thought it didn’t matter much one way or the other. More specifically, he said that he thought that CFAR had a number of valuable resources, that it would be very costly for some outside group to accrue.

So together, we made a list of those resources. We came up with:

- Ability to attract talent

- The ability to propagate content through the rationality and EA communities.

- The Alumni network

- Funding

- Credibility and good reputation in the rationality community.

- Credibility and good reputation in the broader world outside of the rationality community.

My scratch paper:

(We agreed that #5 was really only relevant insofar as it contributed to #2, so we lumped them together. The check marks are from later in the conversation, after we resolved some factors.)

(We agreed that #5 was really only relevant insofar as it contributed to #2, so we lumped them together. The check marks are from later in the conversation, after we resolved some factors.)

Here, we have a disagreement which is something like “how replaceable are the resources that CFAR has accrued”, and we factor into the individual resources, each of which we can engage with separately. (Importantly, when I looked at our list, I thought that for each resource, either 1) it isn’t that important, 2) CFAR doesn’t have much of it, or 3) it would not be very hard for a new group to acquire it from scratch.)

1b: Relevance and completeness checks

Importantly, don’t forget to do relevance and completion checks:

- If all of these considerations but one were “taken care of” to your satisfaction, would you change your mind about the main disagreement? Or is that last factor doing important work, that you don’t want to loose?

- If all of these consideration were “taken care of” to your satisfaction, would you change your mind about the main disagreement? Or is something missing?

[Notice that the completeness check and relevance check on each factor, together, is isomorphic to a crux-check on the conjunction of all of the factors.]

Step 2: Investigate each of the factors

Next, discuss each of the factors in turn.

2a: Rank the factors

Do a breadth first analysis of which branches seem most interesting to talk about, where interesting is some combination of “how crux-y that factor is to your view”, “how cruxy that factor is for your partner’s view”, and “how much the two of you disagree about that factor.”

You’ll get to everything eventually, but it makes sense to do the most interesting factors first.

The two of you spend a few minutes superficially discussing each one, and assessing which seems most juicy to continue with first.

2b: Discuss each factor in turn

Usually, I’ll take out a new sheet of paper for each factor.

Here you’ll need to be seriously and continuously applying all of the standard Double Crux / convergence TAPs. In particular, you should be repeatedly...

- Operationalizing to specific cases

- Paraphrasing what you understand your partner to have said,

- Crux checking (for yourself), all of their claims, as they make them.

[I know. I know, I haven’t even written up all of these basics, yet. I’m working on it.]

This is where the work is done, and where most of the skill lies. As a general heuristic, I would not share an alternative model or make a counterargument until we’ve agreed on a specific, visualizable story that describes my partner’s point and I can paraphrase that point to my partner’s satisfaction (pass their ITT).

In general, a huge amount of the heavily lifting is done by being ultra specific. You want to be working with very specific stories with clarity about who is doing what, and what the consequences are. If my partner says “MIRI needs prestige in order to attract top technical talent”, I’ll attempt to translate that into a specific story…

“Ok, so for instance, there’s a 99.9 percentile programmer, let’s call him Bob, who works at Google, and he comes to an AIRCS workshop, and has a good time, and basically agrees that AI safety is important. But he also doesn’t really want to leave his current job, which is comfortable and prestigious, and so he sort of slides off of the whole x-risk thing. But if MIRI were more prestigious, in the way that say, RAND used to be prestigious (most people who read the New York times know about MIRI, and people are impressed when you say you work at MIRI), Bob is much more likely to actually quit his job and go work at on AI alignment at MIRI?”

…and then check if my partner feels like that story has captured what they were trying to say. (Checking is important! Much of the time, my partner wants to correct my story, in some way. I keep offering modified versions it until I give a version that they certify as capturing their view.)

Very often, telling specific stories clears out misconceptions: either correcting my mistaken understanding of what the other person is saying, or helping me to notice places where some model that I’m proposing doesn’t seem realistic in practice. [One could write several posts on just the skillful use of specificity in converge conversations.]

Similarly, you have to be continually maintaining the attitude of trying to change your own mind, not trying to convince your partner.

Sometimes the factoring is recursive: it makes sense to further subdivide consideration, within each factor. (For instance, in the conversation referenced above about rationality development at CFAR, we took the factor of “CFAR has or could easily get credibility outside of the rationality / EA communities” and asked “what does extra-community credibility buy us?” This produced the factors “access to governments agencies, fortune 500 companies, universities and other places of power” and “leverage for raising the sanity waterline.” Then we might talk about how much each of those sub-factors matter.)

(In my experience) your partner will probably still try and jump around between the factors: you’ll be discussing factor 1, and they’ll bring in a consideration from factor 4. Because of this, one of the things you need to be doing is, gently and firmly, keeping the discussion on one factor at a time. Every time my partner seems to try to jump, I’ll suggest that that seems like it is more relevant to [that other factor], than to this one, and check if they agree. (The checking is really important! It’s pretty likely that I’ve misunderstood what they’re saying.) If they agree, then I’ll say something like “cool, so let’s put that to the side for a moment, and just focus on [the factor we’re talking about], for the moment. We’ll get to [the other factor] in a bit.” I might also make a note of the point they were starting to make on the paper of [the other factor]. Often, they’ll try to jump a few more times, and then get the hang of this.

In general, while you should be leading and facilitating the process, every step should be a consensus between the two of you. You suggest a direction to steer the conversation, and check if that direction seems good to your partner. If they don’t feel interested in moving in that direction, or feel like that is leaving something important out, you should be highly receptive to that.

If at any point your partner feels “caught out”, or annoyed that they’ve trapped themselves, you’ve done something wrong. This procedure and mapping things out on paper should feel something like relieving to them, because we can take things one at a time, and we can trust that everything important will be gotten to.

Sometimes, you will semi-accidentally stumble across a Double Crux for your top level disagreement that cuts across your factors. In this case you could switch to using the Double Crux methodology, or stick with Consideration Factoring. In practice, finding a Double Crux means that it becomes much faster to engage with each new factor, because you’ve already done the core untangling work for each one, before you’ve even started on it.

Conclusion

This is just one framework among a few, but I’ve gotten a lot of mileage from it lately.

(We agreed that #5 was really only relevant insofar as it contributed to #2, so we lumped them together. The check marks are from later in the conversation, after we resolved some factors.)

(We agreed that #5 was really only relevant insofar as it contributed to #2, so we lumped them together. The check marks are from later in the conversation, after we resolved some factors.)