[epistemic status: Tentative. A lot of observation and iteration has gone into this, but it is still probably wrong or misarticulated in some important way.]

This is a followup to, and update of The Basic Intervention Set for Productive Flow, and That, Generalized. In the days after I wrote that post, I mulled over the confusions I note there, and made a new diagram.

But this is also an almost complete outline of my full productivity system. Over the past few months (or longer, depending on how you count), I’ve been writing a something-like-a-book on the Psychological Principles of Personal Productivity. I think this post capture upwards of 80% of that something like a book. [1]

Overview

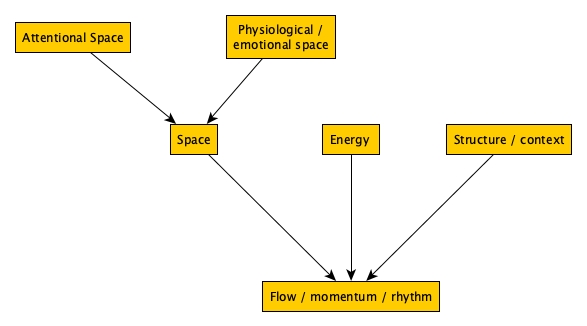

Basically, almost everything that I understand about how to achieve stable personal productivity is summed up in the this diagram:

The yellow boxes represent phenomenological states. I’m sure that each one could be grounded out in neurology or physiology, but I’m not concerned with that (at least right now, in this post). Each one can be thought of as an an axis that compresses detailed information about one’s mental and emotional state.

The pink hexagons represent interventions or intervention sets.

So pink is actions you take, and yellow is goals you hit.

I claim that the four main major state-targets (Spaciousness/ stability / reflective, Mental energy, Clear attention, and Structure / “loaded up” context), are, to a first approximation, both necessary and sufficient for sustained personal productivity. If you have all of these, then productive flow is automatic, if you’re missing even one, things break down, and making progress becomes a struggle.

Therefore, if you structure your life such that have / embody those states by default, and have systems that automatically return to them as set points, when there is drift or disruption, then productive flow becomes automatic.

So in this essay I’m going to outline each phenomenological target, and the interventions that are relevant to it. [Probably each of the interventions deserve their own page, with implementation details, but I’m not going to try for that in this version.]

Caveats

Note that virtually all of the content in this post comes from first person n of 1, phenomenological observation and experimentation. Your Mileage May Vary. In fact, since I no one but me has tried to implement this system, I have almost know idea how idiosyncratic to me it is. I can imagine people who work really hard, and effectively achieve their goals with a quite different internal setup. But this one is designed to make exertion automatic and frictionless, sidestepping the need for internal force. To me, at least, it seems principled, not just effective.

A note on choosing goals

This system is sufficient for getting to productive flow, the state of maintaining high, regular, levels of focus and effort, with the automaticity of water flowing downhill. Maximizing your personal work efficiency.

But that is not sufficient for productivity, that is actually creating value.

The biggest factor that determines a person’s productivity is which problems they choose to work on. It doesn’t matter how efficient you are, how much of yourself and your resources you bring to bear on your work, if your work doesn’t matter.

Productivity = usefulness of work * efficiency of work

So all of the following needs to be put in the context of the huge caveat: Most of your productivity has already been determined by the time you’ve decided on a project. Don’t neglect that step! Figure out what the best thing to do is (or at least which things are in the running for “best”), and only then focus on improving your efficiency.

[Eli, I’m talking to you.]

Clear attention; clear internal, physical/emotional space

In brief, this phenomenological state equals “not distracted.” In order to do deep work, you need to have a clear mental space, so that you can actually commit your full attention to the relevant task. Otherwise, your attention will be pulled this way and that, and you won’t be able to have any deep thoughts.

I’m going to break this overall state down into two components, though in practice the two are interrelated, and on reflection the distinction between them may be unprincipled.

That is, clear attention entails “no mental loops held in memory” and “no emotional hooks.”

Free of mental open loops and niggling thoughts

Here, I am referring to the issue of “holding open loops on the brain” described in detail in David Allen’s Getting Things Done.

[quote GTD?]

In order to clear mental space to focus on the things that you care about, your other concerns and commitments (to yourself and others) have to be stored in a trusted system. Something like a GTD system is essential.

I still remember the immense feeling of relief I experienced the first time I processed all my inboxes. I had had a background sense of not being on top of everything, of not knowing which things I needed to do, what items I hadn’t seen yet, and which one’s had slipped through the cracks and I’d forgotten about. After getting to full inbox 0, that background anxiety evaporated.

You want to be on top of everything that you need to do, in that way, consistently. Sometimes things slip and you find you have more things coming at you than you can track and process, and that’s ok, but this should be a trigger (one of several) for a self regulating system that brings you back to that kind of control. [2]

The actual book Getting Things Done is an excellent resource for this, and I highly recommend it, though virtually everyone I know has needed to adapt its principles into a personalized system, rather than adopting the GTD-system proper, outright.

The other practice in this space that seems to make a big difference, and is similarly accompanied by a palpable sense of relief when I do it, is weekly(ish) scheduling.

(I say weekly(ish), because I’ve lately been experimenting with structuring my life in chunks larger than 7 days: 15 days as an upper bound).

Once every week or so, I make sure to take a few hours and outline the upcoming span on my calendar, scheduling workshops, full focus days, task days, rest days, Deep work blocks, and meetings. [Here is the current version of my span-scheduling checklist. Scheduling a bunch of things is an overwhelming combinatorics problem, and having a checklist really helps. Every time I get confused, I just go back to the last unchecked thing.]

At least for me, I almost always have a bunch of priorities that I care about making progress on, too many for me to manage in my head. This gives rise to a kind of anxiety about not hitting everything that I care about. I’m committed to all of them, and so they interfere with each other: it’s hard to dedicate my focus to any one goal, for an extended period, and sink into deep work, because I’m agitated the other things falling by the wayside. I’m wanting to make sure that everything happens, so by default, everything tries to happen at once, which prevents much of anything from happening. Like Mr. Burns’ diseases.

When I schedule my week, this allows me to sequentialize those parallel processes, such that each one trusts that it will be taken care of in due time, and I can give my full attention to one thing at a time. [Another example of an internal agreement]

Free of “emotional hooks” and unprocessed reactions

The more important class of internal disruptions though, is unintegrated emotional responses, often in the form of anxiety or something like it. (The category of “unintegrated emotions” need a good name.)

For instance,

- I’m agitated because some part of me is expecting something painful to happen.

- I feel activated because I have a partially formed idea that I want to put to paper, and I’m afraid that I’m going to loose it.

- I’m triggered and defensive about something that’s happening.

- I feel generally “urgy” and compulsive, with no superficially obvious reason why.

- I’m distracted, thinking compulsively about my romantic situation, at the expense of much else.

- I’m anxious that something is going to slip through the cracks, or I’m going to drop a ball.

- I’m agitated that I’ll actually be able to do enough math to acquire the math competencies and/or that it will be a boring slog.

All of these involve some part of me that is holding some concern, which in someway distracts or disrupts from highly focused attention. [3]

As I said, these all fall under David Allen’s definition of “Open Loop”, but they differ from the connotations of that phrase in a few ways. For one thing, these ones seem more visceral than “remember to bring in my laundry.” For another, it is often (but not always) much less clear, on the face of it, what the thing is “about.” Also, with these kinds of emotional hooks there’s usually a little pain in the mix, too, which incentivizes flinching away from the thing.

With things of this category, simply offloading them to an external system is probably not sufficient. The part of me holding the concern will continue pulling at my attention and/or affecting my physiology. Sometimes, rightly so, for the concern maybe urgent, higher priority than what I would otherwise be doing, it might be relevant to what I’m doing doing, or if I put the painful/difficult thing out of sight for now, I might continually avoid thinking about it, and not come back to it.

The important thing is that all of the yank at my attention, (or, if not yanking in a particular direction, cause my attention to be generally jumpy).

One major category of unprocessed concerns are Aversions. Aversions are a big deal. My impression is that most of people’s problems with “Akrasia”, “motivation”, and “procrastination” are fundamentally about aversions to their work. (I think this is usually the case, even when there aren’t physiological tells, and when there isn’t an obvious aversive element.) Everything else can be going amazingly, and an Aversion can stop me cold in my tracks, killing my momentum.

Therefore, the most important strut of this whole system is using Gendlin Focusing to process and integrate aversion and other emotional “yanks”. This is so important that it needs to be reliable, both in the sense that there is ~ zero friction to applying it, and in the sense that it works when I apply it. I’ve been working on both of those over the past 3 months.

Very briefly…

My Focusing practice involves a number of different moves that are relevant depending on the specifics of the situation. The core idea is to get to the heart of the thing that’s bothering me, expressing it in its own terms. Sometimes simply articulating the thing cause it to resolve itself. Other times, it gives me footholds into doing debugging, crafting plans, or making internal agreements that the relieve the concern.

A lot of my work is contiguous with doing Focusing: I start out doing the introspection, but this blends into taking action in the moment. Often I’ll act from the the felt sense, letting it steer.

Often action is what’s needed, but sometimes what’s needed it closer to grieving or acclimating to a new expectation (set point) about reality, but some part of me is blocking that, because it seems painful. “Letting reality in”, produces relief. I’ve sometimes pondered that all anxiety is has some dishonesty at it’s core: their either something that you’re trying to reject, or something that you’re trying to project falsely to others.

(I metaphorize that as a vesicle that’s tense, holding something inside, but if you puncture the membrane, the surrounding cytoplasm can get in and the chemical levels equalize. The anxious pressure comes from holding on to something which is not in equilibrium with the world.)

I speculate that in addition to a dialogue practice like Focusing, this overall system needs some way to, gently, top-down, reduce physiological arousal. These felt senses often come with activation, and the activation itself can be distracting / make it harder to make progress on the problem. This is certainly not always the case, often that anxious energy, when properly focused, is super useful. But also, sometimes the most useful thing for me to do in a given moment is take a nap, or to calm down.

I’ve been exploring a few methods in this area, including controlled breathing, and direct manipulation of the felt sense.

Some extra only-kind of related stuff near this category

Expectation of distraction

The two sections described above are relevant to clearing your attention, but there’s at least one other thing that can kill my ability to focus: the expectation of a physical interruption.

This has been discussed at length, but it bears repeating: if you’re trying to do deep work, you need to be in a context that some less-than-conscious part of you expects will not be disturbed.

Dealing with particularly attention grabby things

As an aside, there are a number of stimuli that are attention suckers, like social media, youtube, webcomics, etc.

I find that if I’m engaging with any of these, it is usually because there’s an aversion that I’m flinching away from. (This is also true of TV. If I’m watching TV, that’s a flag that some part of my system has broken down.) But also, they sometimes come up in the natural course of doing stuff.

I’m generally advocating a pretty internal alignment flavored philosophy in this post. I think it is pretty important (and more effective in the long run) to not disown any of your goals. But often the appropriate response is environmental. In this case: block the fuckers.

Personally…

- I have blocked both xkcd and Saturady Morning Breakfast Cereal, my distractions of choice.

- I’ve blocked the youtube feed and recommender sidebar, but I can still use youtube. This is great, because I periodically want to watch a video for any number of legitimate purposes, but it also prevents me from falling into a loop of dazedly watching clip after clip for hours.

- Similarly, I’m using newsfeed eradicator for facebook.

- It would be great if there was I way that I could search my email inbox, without seeing the new email that’s at the top (maybe I can bookmark a link that’s just to my read messages? Apparently, you can search for just read emails, an I could use that to bookmark a link. Success!)

- There are also ways to open blank email to send without viewing your inbox.

Some behavioral interventions that are in this vein, but that I haven’t really got a hang of yet…

- Keeping track of the various pseudo-adictive things, and learning to notice the flavor those urges, so I can be more reflective about them. Things like, “see what’s on my phone”, “check my financial account”, “see if anyone messaged me back on okcupid.” Most of these should have a policy: you check them exactly once a day or once a week, or whatever, with a set trigger (like when you get an email in your inbox.)

- Separating out work that involves searching for information on the internet. Currently, I’ll be doing something, think that I should look something up or see what google says and go do it immediately. But this inevitably turns into a low-value time sink, as I get distracted by all kinds of stuff in the same general area as what I am looking for, and it kills my momentum. A thing that I could imagine doing instead is writing down all of these task, and doing them only after I’ve finished everything else. I haven’t implemented this though, so [shrug].

Psychological Energy

I think most people know what I’m pointing at when I use the word “energy”. Sometimes I have my work laid out in front of me, and I’m free of distractions and…I find it hard to get out of bed. Or sometimes, I know what would be best to do next, and the thought of it is exhausting, and I feel like I have to force myself to do it. In contrast, sometimes pushing hard feels easy (insofar as that makes sense).

Technically, I define psychological energy as “the willingness or propensity to exert cognitive effort” (“cognitive effort”, having its own technical definition). I don’t have a clear enough understanding to know for sure, but I think that it might make sense to think of one’s energy level as the regulator on cognitive effort.

Having ample mental energy is crucial. Some people try and power through life with will power (a loosing proposition most of the time), but if you cultivate your mental energy, you won’t have to force, exertion flows from you easily [modulo the considerations about aversions, and whatnot].

Mental energy seems to break down into, or be predicted by two factors: physical well being, and outlook.

Note that I’ve spent some time looking into the academic literature on mental energy and fatigue, but the following is not that. The following sections, like the rest of this post, are based on my own n of 1 phenomenological investigation and experimentation.

Physical well-being

If you find yourself low on mental energy that could be because of purely physiological factors.

Sleep

Most notably, not getting enough sleep. My ability to function seems particularly sensitive to sleep deprivation, but the cognitive costs of lack of sleep are well documented.

For this reason, a system for stably good sleep is among the most important interventions in this set. [Write a page outlining my suite of interventions on sleep.] It’s hard to get to 100% reliability, however, so it is good to have the ability to compensate for disruptions by taking naps. [Write a page on my updated nap-protocol.]

One re-frame that’s been useful for me: I think of sleep as something like “renewing my connection to the Force.” This seems pretty connotationally correct to me. When I’m well rested I’m just better: I think more clearly, I have abundant energy for enacting my will on the world, I am more alive. Being sleep deprived is like being cut off from the source that nourishes and empowers me.

Thinking about sleep in this light is helpful when I’m up late and engaged in something that feels-urgent in the moment. I remember how much value and power there is in being well rested, and I’m more motivated to put down what I’m doing.

[Notes for future Eli:

- Using rhythm to make up for sleep deprivation

- Napping

- Nicotine

Exercise

I have the intuition that exercise also improves my energy levels. Certainly I often feel great after strength training, in addition to more settled, which seems to jump me into a more productive mode. But I’m somewhat uncertain about the impact of exercise. (Notably, I seem to doubt that it has much impact when I haven’t been exercising, and it seems obviously impactful when I am exercising hard, regularly.)

Intense exercise supposedly improves sleep, giving the former a multiplier effect. (I’m not sure that I exercise hard enough for this consideration to come into play, though.)

[Write about my current exercise processes.]

Rest

Taking rest days also seems to have a large effect. When I take a day off, even when I spend that day doing mentally taxing side-projects, I feel notably refreshed when I return to work. [3] [Note: this is an example of an inner agreement and an outlet policy.]

Similarly, having a 2-hour, 0-commitment, decompression time at the end of the workday seems helpful for maintaining mental energy.

Other

Being physically sick is obviously relevant.

Another behavior that seems depress my energy in the short term is overeating, particularly carbs. Don’t do this.

In general, personal energy depends on general health. Take care of yourself.

Unhanded concerns

After you’ve optimized all the physical influences, the rest of the variation in energy levels is determined by “emotional factors” or outlook.

In particular, it seems to me that low mental energy is a consequence of something being unhanded.

That is, when you have visceral goal or a concern or need that is not being met, and there’s no feasible strategy or meta-strategy for resolving that, your mental energy dries up. Somehow, as long as that concern is unhandled, it is hard to get one’s self to do anything effortful, including task unrelated to the concern.

Therefore, when I find myself sapped of energy (and I’m taking care of my physical well-being), my response is to do Focusing, just as much as when I’m experiencing an aversion. Often, I can uncover what the thing is that’s bothering me and “let it breath.” Sometimes this process releases something on its own. Other times, it gives me footholds for making a plan or a meta-plan that satisfies the undernourished / fearful part.

I’ve sometimes spoken of this in metaphorical terms as “the energy being locked up inside of you”, like it is entwined with the knot that is the unhanded goal. When the knot is untangled, the energy starts flowing again.

Maybe just optimism?

It’s possible that this “mental energy depression is the result of something unhandeled” formulation is too specific. it might be that mental energy simply tracks optimism, or overall outlook. The better you feel about how things are going for you, overall, the more energy you have. [The extreme example being depression, where things seem so hopeless that one can’t muster the energy to get out of bed.]

From an evo psych perspective when things are going well, your system is willing to spend more resources (and take more risks), and when things are going badly for you,

The weird thing is that this is not-domain specific. There’s a single energy level across domains, even though my prospects might vary substantially between domains. For instance, when I feel despair in my romantic life, it leaches my mental energy for making progress on my other projects. A better set up would be, when one goal seems impossible, you double down on the areas that are going well. Indeed, my doomy romantic prospects seem much more likely to improve, if I’m exerting myself in my work life, compared to if I’m laying in bed unable to get myself to do anything. But maybe this is just an inefficient quirk of our evolved minds.

Intra-human variation

I should also note that it seems very plausible to me that humans have a default set-point of mental energy, there is variation in the level of that set point between people, and the processes I’m describing here are on top of one’s individual set-point.]

If so, I would bet that I am relatively privileged in having a high “mental energy set point.” In that case, I’m sorry for your lack of privilege.

That said, I don’t think this is the world we live in, based on other things I know about motivation.

When mental energy falters

I’ve made the claim here that mental energy is extremely important, and you should take pains to cultivate it. But that doesn’t mean that when you’re having bad days you should give up and fail with abandon! (It might mean that you should do less, or take a rest day, but that not the same thing as giving up.

Personally, I don’t refrain from using willpower, but when I do, I flag it, because it means that some part of this overall system has broken down and needs to by repaired and debugged.

“Loaded up” context and structure

If “clear attention” is about clearing away unwanted tugs on your attention, context and structure are about directing your attention towards the things you do want to engage with. Context and structure are actually different things, but they have a mostly overlapping intervention set, so I’m going to treat them together.

“Loaded up” context

I have sometimes had ample mental energy, and be unhampered by aversions or distractions, but still spent most of a day wasting my time on something. There’s a third element which is necessary, which is something like “having the goals you care about, and the action steps that lead to them, mentally present to you.”

You want to have your medium term goals primed, or available in your peripheral awareness, so that they are present to you when you’re making second to second decisions about what to do next, (at what I call “choice points”).

This involves both simply remembering what those things are, and being able to contact the motivational-energy: why you care about them.

In practice, the main intervention that helps me do this is doing daily scheduling, each night (as part of my evening checklist). In this process, I survey the things that I have to do from a fairly high level, where I can make tradeoffs about which things to do in the next day (tradoffs that are hard to make “on the ground”).

Then, outlining my day, and murphyjitsuing it (and making TAPs for some of the transition points as necessary), gives me an opportunity to “future pace”, walking through everything. The next day, I’ll have a sort of “echo” of that plan as I’m going about my day.

I outline my day in my meta-cognition journal, and I am allowed to reschedule things as I see fit, but if I do, I need to note that in the journal and reschedule the things to come afterwards. In theory this is to give me a sense of the scarcity of time, and more clarity about the tradeoffs that I’m making: if I decide to just procrastinate on writing because “I just don’t feel like it right now”, I can see that that means that I’m just not going to do that thing today, or that there’s something else that I’m giving up.

But the main reason I do the re-outlining as I go thing, is that I tried not doing it, and that made my scheduling epiphenomenal: the schedule that I outlined stopped having much connection at all to how I actually spent my day (usually for the worse).

The other thing that I’ve found helpful lately is a weekly-ish list of things to do. This will sound like a todo list, but somehow my way of engaging with this list is unlike any todo list I’ve ever used.

I have a list of all of the shortish-term, medium-sized projects/tasks that I want to get done. Mostly they are sized such that each one will be my main goal for some upcoming day, though some of them are only an hour to two hours of work.

This list gives me a powerful sense of urgency, because I can see the upcoming things, and that I care about them, and that I don’t want them to get lost or fall to the wayside, so I don’t want the list to get backed up by my not doing the thing for today.

Structure

Structure is not actually a phenomenological target, it’s an environmental condition. Context is about setting up your internal world so that there are affordances pushing you toward the things you care about, structure is about setting up your external world so that there are affordances pushing you towards the things that you care about.

Often times, when people have “problems with motivation”, what they really have is a lack of structure.

Basically, structure, as I mean it here, is anything that makes taking some action the default.

For instance, making a meeting with someone (because humans tend to have a higher standard for canceling meetings with other people compared to blowing off an appointment with themselves).

The most extreme version of this is straight up commitment devices, by which you try to constrain your future self using per-committed punishments. I’ve never really used commitment devices, but they seem sort of inelegant. I imagine that most of the time the a person using a commitment device has an unprocessed aversion, but instead of engaging with and resolving the aversion, they just stack the scale on the other side, making it even more aversion to not do the the thing, and thereby powering through the aversion. That sounds terrible, to me.

One bit of structure that I’ve found to be extremely important is a robust, rehearsed transition function for starting focused work. Generally, once I get started, thing fall into place and making progress is much easier. But before I get into the stimulating flow of work, other things can seem pressing or interesting. I’ve sometimes spent an embarrassing number of days without even starting work.

It’s good to make a bulletproofed plan for starting work. It doesn’t have to be the same plan every day, you can more flexibly decide during daily scheduling.

Personally, I usually rehearse the TAP / transition function of starting work as soon as I wake up, or sometimes at 10 AM (after taking some time in the morning). I’ll have pre-decided what I’m going to work on (and opened the relevant document, etc. on my computer, ect.), and where I’m going to do it. And I’ll run it over in my mind, or in physical practice a couple of times.

You probably also want to have very solid structure for a lot of the interventions I’ve talked about here. Sleep and exercise are so important, and upstream of so much else, that it is probably worth it to make the systems that make those things happen really strong, such that, for instance, you do exercise even when you don’t feel like it. (That situation, for instance, might be a good place to use nicotine, even if that’s the only place you use it.)

Spaciousness, stability, reflectiveness

This is the phenomenological target that I am least sure about. It seems like maybe it is just a reflection of the other factors. I’m including it because it seems like there’s something that happens when I make sure I have two hours of 0-commitment decompression time at the end of every day, instead of staying in motion for days at a time.

It feels something like I have more spaciousness, or stability. I’m more able to absorb an roll with whatever comes up internally or externally. This whole system is less fragile. I have more slack.

Specifically this state has the property of making it easier to take the elements of my experience as object. More likely to notice, block / felt sense, and gracefully transition into engaging with it, for instance.

When I “run out of spaciousness” I’m much more reactive.

Also this property allows me to make “stepped back” choices, instead of reflexively reacting to what’s put in front of me. When I have context loaded up, these two, together, represent what I was calling metacognitive space (which is maybe what this state should be called).

I’m not super clear on the relationship between loaded up context, spaciousness without loaded up context, and “stepped back”ness. My current guess is that you could have the lack of reactivity without loaded up context, but in order to be oriented around making decisions optimizing for specific (some kinds of?) goals, you have to load them up.

It’s possible that sort of grace and flexibility is simply a consequence of everything being handled, and nothing additional. That is, when everything is in its place, I’m less on edge, less agitated, in general, and so there’s less pressure to succumb to.

Or maybe this is just one of the effects of being topped off on mental energy. Or maybe something else. This one does seem the most correlated with the other factors.

[Yeah, on further reflection, I think this kind of spaciousness is mostly the result of everything being handled (you trust that everything important will be gotten to, so there’s space to be deliberate about what you’re doing now instead of having a bunch of urges all competing for bandwidth), but is bolstered by the same physiological factors that are casual of mental energy.]

Intense exercise seems to support this state.

Notably, this seems like exactly the benefit that meditation is supposed to confer. So far, I haven’t noticed any particular impact of meditation, and taking a space for a long walk when I am not feeling pressure to do anything helps a lot.

Also, I track all of my time in toggl, which (at least when I was more rigorous about it) was helpful for helping me to be more intentional with my time. That feels like a different thing than this kind of spaciousness, though.

Flow, momentum, rhythm

This is the target of this system, so it seems worth at least mentioning it. There’s a mode that I can get into where things seem to flow, my attention settles deeply into the thing that I’m working on and then moves “snappily” from on thing to the next. Things feel smooth.

There’s an energy, a slight fore-wind pressure, pushing me onward. Things flow, unobstructed.

Actually, I think there are two forms of the goal state. One is something like “controlled overwhelm.” This is when you’re stressed and would be frantic, but you’re attention is organized, and you ride the wave of your overwhelm, letting the energy of the stress push you forward, with enough spaciousness and awareness to respond effectively to, to judo, anything coming at you. Things aren’t handled, but they are meta-handled. This is (according to me) the correct state to be in for most cases of overwhelm. It’s part of the control system that gets you back to closer to on top of things.

Secondly, there’s the equilibrium state of being centered and calm, but energized, speeding up and slowing down as necessary, where everything is handled. That looks like what I described above.

Review and conclusion

- The goal is extended, high quality focused attention (Deep Work) on the problems you care about.

- The equilibrium state is “everything is handled.” This is really important.

- A lot of how this is reached is internal agreements.

- Systems that make the intervention level automatic, make everything else automatic.

[1] Some pieces that are left out, but which I think are important, are…

- How motivation works

- Hedonics, micro-hedonics, and boredom

- Insistence on not squandering time

- TAPs for state-regulation

[2] One, semi-related trick that I like: when I feel overwhelmed with everything that I need to do, I’ll write out all of the things on index cards. This way, I can spread them out on a table, and take stock of all of them at once, and then prioritize them, and put them in a stack, so that I can only see the top one (the task that I’m focusing on), at any given time.

[3] I note that all of these are “uppers”, in marked contrast to symptom of being low on mental energy, which (as I postulate later) is also a matter of unhanded, unintegrated concerns. Are these perhaps fundamentally the same thing, but sometimes manifesting as excess activation (potentially maladaptive, preparation to fight or flight) and sometimes manifesting as dampened activation (for some reason)?

Further, does settling into deep work requires a Goldy-locks sweet spot of the right amount of physiological activation? Or is it just that you can’t be activated and have other concerns pulling at your attention, because then your attention will switch between them. High activation and mono-focus is fine?

[4] This suggests to me that mental energy is, at least in part, a cost of stress or top-down focused intention. It may just be that exerting mental effort is, well effortful, and the subsystem that governs effort allocation is only up for it if it expects to get a reprieve in short order. Otherwise, it refuses to allocate the relevant mental resources.

I grant that this seems to be passing the buck on why overexertion of effort is to be avoided and why a reprieve is good. A literal energy cost seems implausible, but it might be due to the costs of continual high arousal (which correlates with cognitive effort), or maybe because there are mechanisms that need processing / consolidation / diffuse mode time following application of focused attention (maybe because focus attention overrides a bunch of competing processes in the parliament and they need to stick their head up and do some processing to confirm / repair* / update their strategies, or maybe because focused attention / intention entails a lot of data input, which needs to be processed for learning to occur).

* – The idea being that you’re making a bunch of updates in a bunch of different areas throughout the day, and some of those updates would break, or interfere with some of your existing strategies. So one of the things that is happening in defuse mode processing is those strategies are themselves adapting to the new updates, so as to still be functional. Total speculation.